Momauguin and Half Mile Island: An Historical Journey - Part I

CHAPTER 1: Let Us Step Back In Time To The Early 1600s

Long before the arrival of Europeans, Connecticut was populated by a multitude of American tribes, including the Quinnipiac, a coastal branch of the Algonquin whose language they spoke. Within the Quinnipiac there were four groups: the Momauguin, living along the New Haven shore; the Montowese in North Haven, the Shaumpish in Guilford, and the Totoket in Branford. Our story begins with the Momauguin and their migration to East Haven.

Before English colonists arrived, the coastal Momauguins numbered about 250 members. Living off the water and the land, they pursued a variety of activities: fishing and clamming; farming of beans, squash and corn; and gathering of nuts, berries and roots. They also hunted game animals and birds.

They lived in wigwams covered with rush mats, skins or bark. Travel was by foot or dugout. Clothing consisted of tanned hides decorated with feathers, porcupine quills, and shell beads.

The East Haven group was led by Momauguin, the sachem (leader) of the tribe at the time of English colonization of New Haven in 1638. His family included the tribe’s most prominent leaders: his sister, leading the Menunkatuck, and his uncle, the sachem of the Totoket.

Their culture, blood relationships, and belief in a higher spirit kept them together. Little is known about their spirituality, except that they practiced rituals and ceremonies showing respect for an inner power they believed existed in all things. They believed in multiple deities such as the god of the sun, the moon, and the skies. According to their beliefs, after death the souls of both good and evil left for a spiritual dwelling in the southwest where they enjoyed an afterlife like their time on earth.

Chapter 2: The Colonization of New Haven

It was quite challenging in the 1600s to move from England to New England. There were no stores or shops to buy provisions, building materials, and furniture. There were no supermarkets or hospitals. There was no Starbucks! Migrants to the new world had to bring everything with them: furniture, bedding, clothing for all conditions, cookware and plates and knives, books and candles. They brought all manner of tools. They brought cows and sheep for their milk or their wool. When ready to leave, they said their goodbyes, knowing full well that they were leaving forever, to live, die and be buried in a strange land.

In the early 17th century, thousands of English Puritans colonized North America, mainly in New England. Puritans were generally members of the Church of England who believed that the Church of England was insufficiently reformed, retaining too much of its Roman Catholic doctrinal roots. In 1633 King Charles I appointed William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest office in the English Church. Both men hated the Puritans and treated them harshly, with many Puritan ministers arrested for their views. Eventually it came to pass that two such Puritan ministers, John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton, decided to escape to the new world: Mr. Davenport because he was a known and troublesome Puritan, and Mr. Eaton because he was a wealthy man and secretly a Puritan afraid of being found out. By 1637 they were ready to depart. After months at sea, they arrived in Boston where they found the people open and friendly. However, there were signs of religious persecution and the appointment of an English governor of the Massachusetts colony by the King was pending.

And so, the good ship Hector along with a companion ship left Boston in the Spring of 1638. They planned to sail to a place called Quinnipiac.

Mr. Eaton’s good friend, Captain Stoughton, had recently visited the area while chasing the Pequot Indians during a fierce war. The captain had described the fine harbor and rivers that emptied into it, as well as broad rich meadows, as the best place for a settlement that he had ever seen.

That same November, they signed a treaty designating the eastern side of the harbor as a reserve for the Momauguin band. The remaining lands were formally transferred to the British.

In the early years, the settlers and natives enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship. Unskilled in hunting, the English traded for deer meat, and learned to fish using weirs (dams) to catch fish. The natives served as guides and messengers, hunted predators that killed livestock, and taught the settlers how to fish and clam.

By the 1660s, the natives found it challenging to grow sufficient crops on their lands to sustain the tribe. They offered to buy back some lands to increase their harvests, but after some debate at a town meeting, in 1657 the town rejected the offer.

Despite the strained relations, there remained a mutual interest in a military alliance. As more and more wars with neighboring tribes occurred, the tribe’s population continued to decrease. Over time they sold off more lands to the colonists and the English settlement expanded, consuming nearby forests and natural resources needed by the tribe.

In 1675 the Quinnipiac joined the colonists in fighting King Philip and the Wampanoag, who were aligned with the British. The Quinnipiac lost nearly two thirds of their population and, upon returning home, found the colonists had built a fort around their remaining properties and refused entry to any native. They were eventually exiled from lands that had been theirs for generations.

As of 1774, only 71 natives remained, and they were further decimated on July 5, 1779, fighting side by side with the colonists against the British invasion of New Haven. In 1850, the last of the Quinnipiac tribe died. There are still natives of Connecticut who have Quinnipiac ancestors, but there are no known full-blooded Quinnipiacs left.

Life wasn’t all about Indians, settlers and life under a British King. Colonists feared outsiders and witches as well.

Click here for a brief story about the witches of Dark Hallow and “jack o’ lanterns”.

Momauguin and Half Mile Island: An Historical Journey - Part II

Chapter 3: The Birth Of An Island

James Michener’s novel Hawaii begins with a hauntingly beautiful tale about the birth of an island: The receding waters, the land formation, and the arrival of a people prepared to build a life and a culture. We are such a story!

In 1866, sixteen years after the death of the last full-blooded Momauguin native American, “Half Mile Island,” as it was then called, was still an inaccessible wilderness. Bordered by Bradford Creek to the west and the Farm River to the east, the only land access was a narrow horse trail that would later be called Cosey Beach Avenue.

At this time, Daniel Palmer built the first home on what is now known as Whaler’s Point, or approximately the top third of the island. That home exists there today, although greatly altered. After the Palmers moved to the East Haven green, Mr. Palmer still owned most of Half Mile Island.

That same year, Dennis Mansfield, after roughing it on the island for several years, decided to start a shore resort facility. Renting three of the southern acres, Dennis built boating, fishing and hunting facilities, as well as a home for his family. He carved out a primitive road from Short Beach Road to accommodate horse-drawn stages and wagons. Soon he and his wife were selling lobsters and shore dinners to boaters and sportsmen. By the 1870s his resort became known as “Mansfield Grove.”

The Mansfields built the two-story Rocky Point Hotel in 1879 which featured a dozen upstairs bedrooms, a sweeping veranda, and plentiful rocking chairs for guests to relax.

When Dennis died in 1889, his estate was divided into three sections that eventually became what we have today. The twelve northernmost acres and cottages became Shepherd’s Grove (now Whaler’s Point); The remainder, which included the hotel, three cottages and a boathouse, as well as fourteen boats, two fish cars, three horses, seven cows, six pigs, etc., etc., became the property of Caroline Mansfield, who carried on the resort’s operation. The hotel survived the hurricane of 1938, and finally met its end when it burned down the following year.

CHAPTER 4: The Industrial Revolution

Now our attention turns away from colonization and towards the Industrial Revolution and the entrepreneurial spirit that characterized the time period. While historians may disagree on exact dates, Connecticut entered the industrial age sometime around 1780 and fully embraced it between 1820 and 1830.

The Farm River was essential for many local commercial enterprises. It has been used for navigation by a fertilizer factory, stone quarry, paper mill, saloon, salt hay harvesting, and by fishermen and boating enthusiasts for centuries. During colonial times it served as home to a swine farm, and even an elevated area known as Beacon Hill sported a lighthouse for safe navigation downstream to Long Island Sound.

Farmers raised cattle and horses primarily for their hides, and shoe making became an early and extensive business along the river from New Haven almost to the coast. At first, sweepers used to sweep trimmings into the water; eventually the smell of rotten leather became overpowering and city fathers had to fill in the riverbanks.

The low frame building on the west bank of the Farm River on Route 1, across from the Twin Pines Diner is the site of the first Iron Mill in Connecticut, and the third in the United States. Established in 1655, the forge was converted into a fulling and carding mill in 1687 by Samuel Hemingway. Over the years the building has been used as an antique shop, laundry, and tea room; recently opened as a European restaurant, Transilvania Restaurant & Bar.

Before 1832, as cattle and horse ranching moved to the “wild wild west” with its open prairies suitable for larger herds, ranching became marginally profitable on the east coast. However, local farmers found an opportunity to raise dairy cows and opened milk producing businesses. Two local businessmen, H. Todd and W. Townsend, decided to bottle milk and deliver it in capped bottles. Customers rinsed the empty bottles and returned them to the same delivery wagon on its next return. And so, here in East Haven, bottled milk was invented and recycling was born. Home milk delivery became an industry model well into the 1960s.

In various locations between North Haven and Branford, there were in these times quarries producing vast amounts of high-quality trap rock. While some was transported by land, most was transported down the Farm River to the Sound. In the Twentieth Century a New York concern bought the quarry to eliminate its competition. Eventually the quarry burned and was closed. Remnants of the ruins exist today along the trolley line.

The land on East Main Street at the foot of Lake Saltonstall was used for a variety of businesses until it was sold in 1681 and converted into a sawmill, turning out planking for wooden ships built in local shipyards on the banks of the Quinnipiac River in Fair Haven. By 1873 it was operating as a brush factory as well, until 1878, when the grist mill, saw mill, and brush mill were all destroyed by fire.

CHAPTER 5: Trolleys and Model “T” s

Originally population growth in greater New Haven was driven by the flow of immigrants fleeing persecution or famine. Others arrived out of a sense of adventure and opportunities in the new land. In 1890, Momauguin was still mostly a wilderness, with only a few sparse farms in the area. Most of the industrial growth surrounded the farms. Except for water access, Mansfield Grove could still only be reached by horse travel over the narrow and primitive road cut out over 25 years earlier. The future of the Mansfield Grove resort did not look promising, lacking the charm and personality of the late Dennis Mansfield. But things were about to change.

According to New Haven Streetcars, a publication of the Shore Line Trolley Museum, “The first street railway began operation in New York City in 1832.” “In May 1861, more than a year before the nation’s capital introduced this new mode of transit, the forty thousand residents of New Haven were furnished with local rail transportation. Street railways made it possible to reach both residential and manufacturing areas.” Thus began a transformational era which saw New Haven’s population more than quadruple between 1861 and 1948.

The initial form of transportation was horse drawn stages, and by 1883 the rails were extended from the East Haven green to the shoreline resorts. This completed the connection between the shore and the New Haven green on Chapel Street. Lake Saltonstall was a transfer point from New Haven to points east. Once the resorts there closed, ridership suffered, and by 1898 a line was extended down Hemingway Avenue to the beach. In order to induce summer riders, the Momauguin Hotel was built and lavishly furnished, including sterling silver table settings from Tiffany’s. All was destroyed in a fire in 1911.

After the 1911 fire, the trolley company extended the rails along Cosey Beach Avenue, terminating at the Bradford Creek foot bridge providing access to the Mansfield Grove Hotel (currently the site of the Four Beaches Condominiums). In later years it was known as the Rocky Point Hotel and was well known for its illegal rums during the Prohibition years.

After the turn of the century, while the trolley company sought ways to sustain ridership, a new form of transportation independence struck the country like a storm. Henry Ford’s “Model T” automobile offered affordable transportation to the average American, free from the constraints of rail lines and the confines of schedules. Between 1913 and 1927, Ford sold more than 15 million cars.

After World War I, the automobile began to reduce trolley ridership. To offset this, around 1922, the trolley company encouraged the construction of a dance hall on Mansfield Grove. Once built, the hall saw many uses, from dances to church services. On weekend afternoons one-reel movies were shown, accompanied by the piano player who could adapt the music from action to romance, or to the charge of cowboys and Indians. Later the hall was used for roller skating, and eventually as a restaurant night club. With the great band era just beginning, Rudy Valley, Cab Calloway and Glenn Miller toured here, as did other celebrities of the time.

Eventually the dance hall burned down and was razed; the tracks were removed from the streets to accommodate cars. No more would young boys hang on the back of the trolleys, stealing a ride and catching the ire of the motorman when he spotted them.

Momauguin and Half Mile Island: An Historical Journey - Part III

CHAPTER 6: The Good Old Summertime

Many nearby shoreline towns enjoyed quiet winters and hectic summers. For example, Bridgeport had “Pleasure Beach,” Milford had “East Broadway,” West Haven had “Savin Rock,” and East Haven had “Cosey Beach.” Each in their heydays had their own personality but shared people’s love for fun, good food, great music, frolicking in the sun, and blowing off steam.

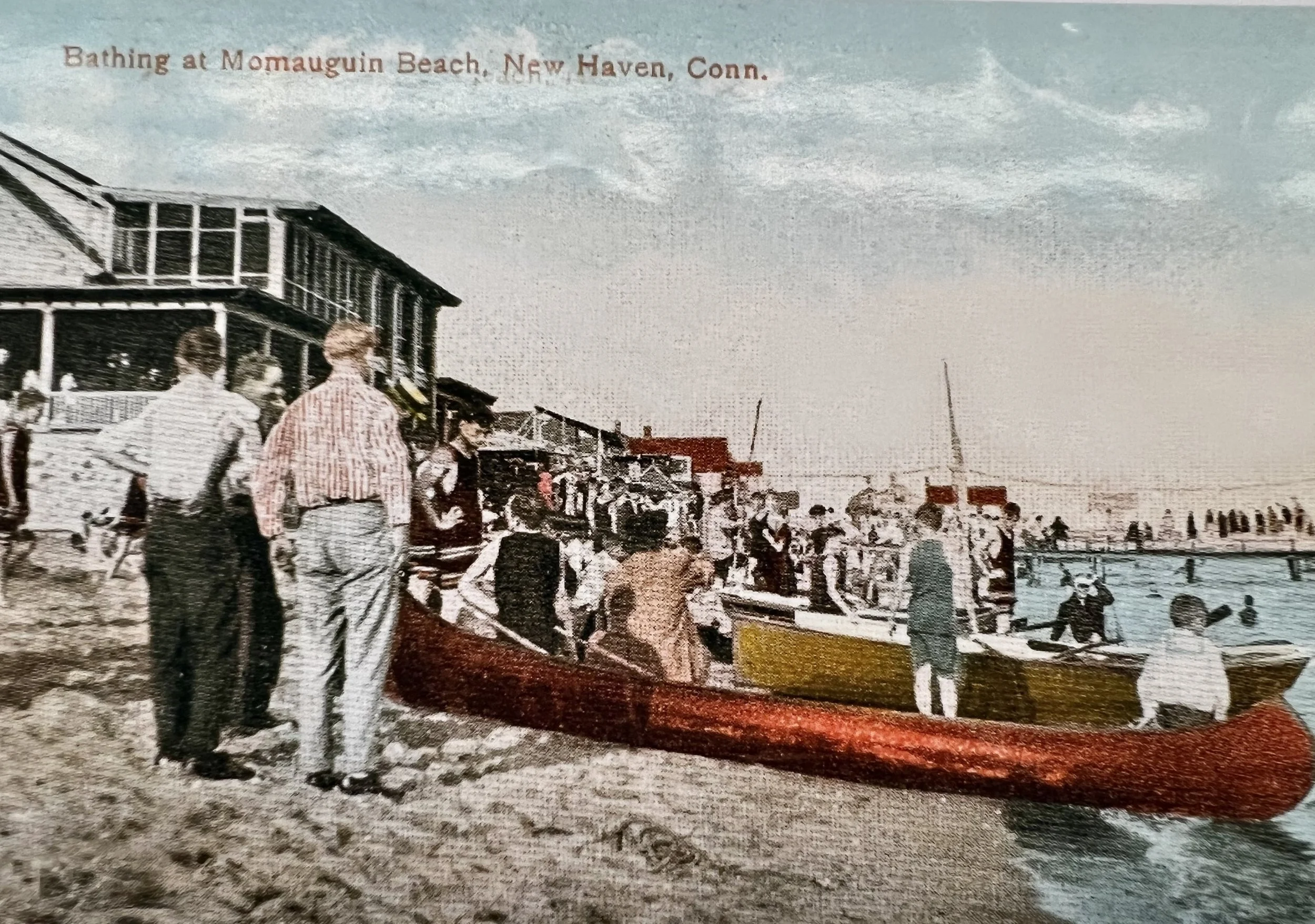

As trolley lines were extended to the water and auto ownership quickly grew in popularity, the East Haven beaches continued to offer families a great option for summer weekends and vacations.

If you wanted to see the area, you simply took a seaplane ride off the beach at the Momauguin Hotel.

In the 1920s, for five dollars, one could obtain a seasonal license to operate a pool room, a Chinese Laundry Game, an arcade, any number of games of chance, or simply an ice cream stand. During Prohibition, licenses strictly regulated the sale of “temperance drinks,” although it was common knowledge how to visit some dark back room or cellar for some Santa Cruz rum recently floated in oak barrels to the shore in the dark of night.

No one spends time at the beach without food and drink. Sidewalk stands, restaurants, and the hotels all offered options to quell any size appetite. Charlies Lunch, known for its chowders, and possibly made from a converted trolley car, was situated on the left and northerly side of the “car bridge” crossing onto Mansfield Grove, possibly where the entrance to the 2 Mansfield Grove Road garage is today.

Rossiter’s Clam Bakes, Sheep Bakes, and occasional Possum Bakes were held on the hill (which we can assume is where the cottage campers exist today) and were very well attended. Charles, J. H. Rossiter’s son always made sure plenty of chowder was sent up to the hill for the clam bakes.

William (Billy) Ashmore worked for Seamless Rubber Company in 1926 and was probably laid off during the Great Depression. To make ends meet, he and his wife took over Charlies Lunch, changing its name to Billy’s Restaurant, and eventually he moved across the creek to what was then Jenny’s Tea Room at 3 Cosey Beach Avenue. New owners Orlando and Josie Orifice named the restaurant Beachhead in 1942 and bought the property in 1944.

Local historians have written that the Beachhead had multiple owners over the years before the latest change in name and ownership as The Lobster Shack. For readers who follow such details, some of the owners included: Orlando & Jessie Orifice 1942; Neil Vigliante 1971; Pasquale Criscuolo 1978; Angelina Criscuolo 1986; and Ms. Fucci and Ms. Bucci in 1994.

The restaurant business is notorious for name changes and failures. Cosey Beach restaurants and inns were not immune to such events. Here are a few additional pictures of restaurants at the beach.

One of the oldest and most talked about venues was Don’s in Mansfield Grove. At times a restaurant, a dance hall, a music venue and a skating rink, it was a favorite watering hole for Yale Alumni Associations and always popular for frozen custard on a steamy August afternoon.

Cab Calloway, Rudy Vallee, Guy Lombardo, and Glenn Miller are notable celebrities who performed here on tour. After Don’s was converted to a skating rink, other venues took its place. In the 1960s for three dollars, a high school senior and his date could enjoy an after-prom party at the Horizon Club, featuring music by Tommy and The Rivieras.

After the turn of the 20th century, primitive bath houses and changing rooms were supplanted by well designed changing rooms on the beach or at businesses like the Sea Spray Baths on Cosey Beach Avenue. There is nothing better than the sun on your face, the wind at your back, and a day at the shore.

This is one of several paintings donated to the East Haven Historical Society by the family of Margaret (Peg) Mansfield, a local artist, whose possible lineage to settlers Dennis and Caroline Mansfield could not be determined.

Cosey Beach was well known for entertainers on tour and locals at the beach. In 1955 this reputation resulted in using the beach to promote the movie ”It Came from Beneath the Sea.”

CHAPTER 7: A Summer Playground

In the January 10, 2012, issue of The Patch, the lead article describes the campers’ community as a magical place where “for almost 100 years generations of the same families” have turned the community into “a summer playground.” Camping on the hill had humble beginnings in the 1870s, when Dennis Mansfield created a modest resort and rented roughly seventy haphazardly placed camp sites were rented in the early years primarily to hunters and outdoorsmen. For those less inclined to sleep under the stars Mansfield built the two-story Rocky Point Hotel, complete with restaurant and water views.

By the end of the century trolleys made the resort more popular with families. After World War II and the rapid growth of automobiles for leisure trips, the more primitive sites were gradually replaced by surplus Army tents, typically 10’ x 16’ square.

One local historian and resident of the campgrounds was George Uihlein, one-time president of the Southern Connecticut Gas Company. In one of his many historical writings he shared a memory from the 1920s:

“One of the most exciting days of my early childhood was the day after school closed in June when my family would move to the shore … That morning we loaded the truck with most of our camping needs … the World War I surplus Army tent and pole, kerosene stove, dishes, pots and pans, an icebox, table, chairs, beds and bunk beds, two chests of drawers, etc. The trunk was piled high, with everything held on by ropes … I got to ride with my father and Mr. Wark in the cab (of a rickety old Model T truck,) my sister Ellen and Mom took the trolley car.”

Families returned to the same spots year after year. Tents were improved and enlarged; porches were added to many. Eventually people wanted to convert tents to cottages, adding indoor plumbing, sewers, and town water. Jesse Bartlett, then owner of the land, gave his approval for the conversions, insisting that cottages retain the original footprint of the tents they were replacing.

In 1966 the property was purchased by the “Mansfield Grove Campers Association Inc.” The members of the Association were cottage owners who had been renting the property. The Association owns eight acres of campground plus four acres of wetlands to the north. The campground is sandwiched between Whaler’s Point to the north and Four Beaches Condominiums to the south. With direct waterfront views and access to a private beach, it is no wonder that many of the cottages are owned by the same families, generation after generation.

Momauguin and Half Mile Island: An Historical Journey - Part IV

CHAPTER 8: Fires and Floods

Since the beginning of time, fires have played in important role in shaping our communities. Fires have been caused by nature as well as humans. An accelerant and a match can be as damaging as a lightning strike. These phenomena are not foreign to our shoreline. Human-made fires are driven by financial or personal gain, or an adrenaline rush; and we have seen it all.

Early in the twentieth century the Momauguin resort community experienced some dramatic fires. In the summer of 1911, a multi-building conflagration destroyed the Momauguin Hotel, the Hoyton Hotel, and all the other buildings in their complex. As fate would have it, the volunteer fire company’s hose cart was stored in the hotel basement, thwarting their attempts to quell the blaze.

Understanding the need for an improved fire service, the community formed Cosey Beach Fire Department, but before they were ready, an arsonist named Edward Janey Tulley, the hotel’s night watchman, torched the buildings he was responsible for protecting.

Later, the Sea Spray Bath building was built on the spot, now the location of the Town Beach. When the property burned thirty years later, the blaze was visible from Long Island, where residents called the East Haven Police to see if the town was on fire.

The list goes on, including an airliner crash in 1945 in the south end, as heavy fog caused a plane approaching Tweed to undershoot the runway and strike several homes. Despite emergency assistance from area towns, four houses were destroyed and twenty-eight people died. This was one of the few fires causing loss of life.

An evening fire in 1951 destroyed the Silver Sands Hotel, which was replaced by the Wexler Day Camp, subsequently sold to Arnold College, and finally Camp Adventure, a summer camp for children.

Between 1971 and 1973, there were approximately thirty fires, all deemed “suspicious” and involving empty summer cottages. Many of the occupied cottages were rented and those residents showed little concern, while the owners expressed some concern for their properties but less so for human injuries. Subsequently, the state police investigated twenty of those fires, closing fifteen with juvenile arrests.

The same story was playing out in the 1960s and 1970s across neighboring shoreline communities. Milford had an active arsonist for many years as did West Haven. During this time, Bridgeport lost the Pleasure Beach Ballroom to fire.

Everyone has tropical storm stories to tell. This writer recalls one time in the 1950s, recklessly posed standing on a seawall during the height of a major hurricane, solely so his uncle could take pictures of the waves more than ten feet high crashing effortlessly over the seawall.

While completing research for this chapter, this writer noted that one interesting comparison between fires and floods is the sheer power nature holds over us mortals. Most of the fires caused damages in the tens of thousands of dollars, while hurricane and tropical storm damage was estimated in millions of dollars. Look at some examples:

In 2012, Super Storm Sandy caused more than 630,000 power outages and $360 million in damage.

In 2020, Tropical Storm Isaias did more than $21 million in damage and caused two deaths.

The “granddaddy” of all hurricanes to reach our shores was when “The Great New England Hurricane” (also known as “The Long Island Express”) hit in 1938. The storm formed off the coast of Africa on September 9, becoming a Category 5 before making landfall on Long Island on September 21 as a Category 3 storm (although some sources disputed the rating as underestimated).

Across New England the storm caused more than 682 deaths, damaged or destroyed more than 57,000 homes, caused additional damage to roads, commercial properties, and other infrastructure. Damage estimates ran as much as $410 million, and damaged trees and buildings were still visible in 1951. In all of recorded time, perhaps the only prior storm to eclipse the “hurricane of ‘38” was the “Great Colonial Hurricane” of 1635.

CHAPTER 9: Decay and Renewal

Urban decay doesn’t have a singular cause, nor does it have a specific start or end date. It simply sneaks up on the community. The cumulative harm caused by fires and storms is highly visible and often long-lasting. In many instances, owners choose not to rebuild, hopeful to someday recover their investment through land sales.

As the number of boarded up homes grew, portions of the shore became increasingly marginal. Cosey Beach and surrounding areas succumbed to an exodus of stable families, replaced by less responsible renters. The entire country was troubled and East Haven was no exception: a divisive Vietnam War, gas rationing, civil disobedience (this might be a good time to rent the movie Hair), and questionable political leadership all contributed to decline. Slowly, as the area continued its decline, businesses failed and Cosey Beach and Mansfield Grove were less appealing destinations on a sunny summer day.

Several newspapers’ articles of the times similarly described life at the beach. From reporter Toby Schwartz: “This past Fourth of July weekend was fairly quiet … only two houses were torched, and a couple of new lifeguard stands … were turned into a holiday bonfire.” The July 20 ,1977, New Haven Advocate carried a similarly themed article including quotes from a local businessman who, comparing 1977 to summers six or seven years prior, said “Back then, people were friendly. They’d wave from across the street, come over and chat, everyone knew each other. Now they’re scared. … They don’t come to the beach like they used to.”

Over the past one hundred plus years, there have been multiple ups and downs in housing, economic development, business mix, governmental oversight, population mix, etc.

Our goal is to provide you with some insight into attempts to maintain a vital and vibrant shorefront. Therefore, there has been no attempt to dig into the annual blow-by-blow of development details. We’ll start at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. From Bradford Avenue to Austin Street, and from Coe Avenue to the Bradford Creek was considered Bradford Manor. Sometime around 1910 the Wilkenda Development Company developed this area. Three streets (George, Henry and Steven) were named after three principals in the venture. Some of you may recognize their law firm, Clark, Hall & Peck. Early maps may depict some areas with different names; Coe Avenue used to be Momauguin Avenue, and Cosey Beach from the Town Beach to the creek was called “No Man’s Land.”

In the early 1920s, multiple developers offered shorefront and nearby building lots. Momauguin Heights started at the Sound and encompassed Hibiscus Street and Palmetto Trail. Print advertising offered free transportation from New Haven, beautiful free presents, and promised good value. You could even make partial payment with your Liberty Bonds (as U.S. Savings Bonds were known in those days). Zero interest easy payment terms were available.

Following the Mansfield Heights development, Mansfield Park was offered with lots priced as low as $99.00, and most costing no more than $1,500.00, all free of interest or taxes for one year. Buyer friendly terms included a ten percent down payment and weekly payments between $2.00 and $5.00.

The town planners were periodically drafting redevelopment plans for the shoreline. One such 1952 plan encompassed the area from the Town Beach to Whaler’s Point, and from the water to Bradford Avenue.

Town planners knew they were ill prepared to manage the scope and complexity of renewing 500 plus acres of mixed-use buildings and blighted conditions. Enthusiastic planning soon changed to small scale efforts, such as an expanded Town Beach and formation of a shoreline association to manage change. The Momauguin Redevelopment Agency, formed in 1952, was disbanded in 1955.

According to a 1976 Journal-Courier article, talk in the mid-1960s would “revitalize the Momauguin area with apartments, beach clubs, restaurants and shopping centers.” Developers began to buy up land, and soon detailed plans were considered. One such version, as described in an earlier 1971 New Haven Register article, included “the addition of three 17-story apartment towers at one end and five 10-story apartments at the other end.”

Town planners in the 1960s were meeting with HUD (the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development). One consequential decision was to completely rebuild the center of town and then work on other areas of town. By the time the downtown projects were competed, funding had dried up and the Momauguin plans were abandoned.

Momauguin and Half Mile Island: An Historical Journey - Part V

CHAPTER 10: From Tribal Lands to Luxury Condos

Our journey through time began more than 400 years ago when Half-Mile Island was the home of the Momauguin tribes.

We witnessed the arrival of the English settlers (Puritans), the demise of the Momauguin, the Industrial Revolution, the evolution of automotive and mass transportation, and the evolving character of the East Haven shore.

In the previous chapter of this story, we explored how humans and nature conspired to bring both fortune and failure to the people and the land. We also witnessed a failure of developers, investors and government to create, fund and implement shoreline development in the most cost effective and sustainable ways. Half-Mile Island changed ownership multiple times, beginning with the 1800s ground-breaking of the shore resort by Dennis and Caroline Mansfield, and ending with sales to developers in 1973.

It was the mid-1980s before construction of Four Beaches began and units were ready for sale. The complex was featured in a New York Times article on September 13, 1987:

Nolan Kerschner, one of Connecticut’s best-known condominium developers, is building waterfront homes for a new kind of buyer: the affluent elderly.

Such buyers are increasingly attracting the attention of residential developers and builders in Connecticut. It is a market made up not only of successful local people…but also of New York residents…eager to enjoy a more leisurely living environment while retaining easy access to business endeavors in New York City.

There was a shortage of similar properties “as the result of a white-hot residential market that had prevailed, until recently, for all types of properties through-out the state for more than four years – the outcome of an economic boom that began in the early 80’s, is still continuing and shows no signs of slowing down.”

That last statement is a bit misleading, as The Times goes on to say: “By this spring, however, the market had settled down, dampened somewhat by a buildup of inventory”. The Tax Reform Act of 1986, which encouraged investors to sell vacation and rental properties, rising interest rates, higher prices, and the leveling off of peak demand, created a slowing market and more competition for sales.

When Building 1 was completed, model units were furnished, open houses scheduled, and a sales office was open seven days a week.

The economic slowdown was not kind to the Four Beaches complex. As was the case with many other projects, developer and builder bankruptcies brought construction to a halt. In 1989, on a warm and sunny Sunday afternoon in late June, 35 new, two- and three-bedroom units were sold during a real estate auction.

Twenty-six years later, time and weather had taken their toll, and the complex was in an advanced state of disrepair. The long-term decline was not lost on the Four Beaches Association Board of Directors. As early as 2012 architectural and engineering studies were drawn up creating a vision and pathway to comprehensive improvements to the complex. By 2015 these plans had been put out to bid, financing secured, and at a Special Meeting of the owners, the improvements were approved.

Today, the visions of various developers as far back as 1973 have been realized and exceeded. Perhaps The New York Times said it best: “Set between the East Haven salt marshes and the Thimble Islands is a rocky 10-acre peninsula that cuts deeply into the choppy waters of Long Island Sound. On this outcropping, bounded by sandy beaches and festooned with dune grass…” are “waterfront homes for a new kind of buyer.”

Thank you for joining us on this historical journey. We hope you have enjoyed it as much as we have enjoyed bringing it to life.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the East Haven Historical Society for full access to their archives and museum. Special thanks to Melanie Johnson, Curator, and Paul Garneau, Treasurer, for sharing their expansive knowledge, patiently responding to our endless stream of research requests. Thanks also to Society members George B. Uihlein, Cliff Nitchke, and Bill Ward for their writings. For more information click on the photo to the left.

Athey, Mary. “Residents Create Magical Summers...” Patch, 18 Jan. 2012.

Brooks, Andree. “Connecticut: In East Haven, Waterfront Condos Are Designed for the Affluent Elderly.” The New York Times, 13 Sep. 1987.

Leeney, Robert J. An article regarding “…the history of the Mansfield Grove Campers Association…” New Haven Register, 15 Sep. 2001.

Mingrone, Bill. “Momauguin rejuvenation plan…” The New Haven Register, 23 Oct. 1973.

Merritt, Grace. “Condo on the Sound outweighs the risks.” The New Haven Register, Undated.

McNulty, William. “Momauguin: A Brief History.” The Momauguin School, 8 th Grade school project, circa 1951.

“Life of the Quinnipiac tribe.” The Quinnipiac Chronicle, 28 Nov. 2002.

WS-ADMIN. “Dark Hollow and other Spooky Tales.” newhavenmuseum.org. 30 Oct. 2020

Information, most notably the “Simplified Timeline of the Property Owners of Mansfield Grove,” included in the Blue Book, published by the Mansfield Grove Campers Association, Inc.

Project Manual “Exterior Renovations at Four Beaches Association.” Community Planners, LLC, 17 Dec. 2012.

Project Manual “Building Envelope Study for the Four Beaches,” Community Planners, LLC, 24 Jun. 2012

Various Four Beaches sales materials (1986-87) and auction packages (1989) were retrieved from the Association archives.

We would like to express our appreciation to the many Four Beaches residents who provided information, pointed us to various resources, or offered valuable insights which influenced the completion of this project. With apologies to anyone omitted in error, special thanks to Rick Perachio, Elizabeth Stein, Jack & Leslie Loehmann, Robert Baldini, Barbara Natarajan, Joan DeFosses, Barbara Vietzke, and Linda Esposito.

LaMar, Maribeth, and Justin