Momauguin and Half Mile Island: An Historical Journey - Part II

Chapter 3: The Birth Of An Island

James Michener’s novel Hawaii begins with a hauntingly beautiful tale about the birth of an island: The receding waters, the land formation, and the arrival of a people prepared to build a life and a culture. We are such a story!

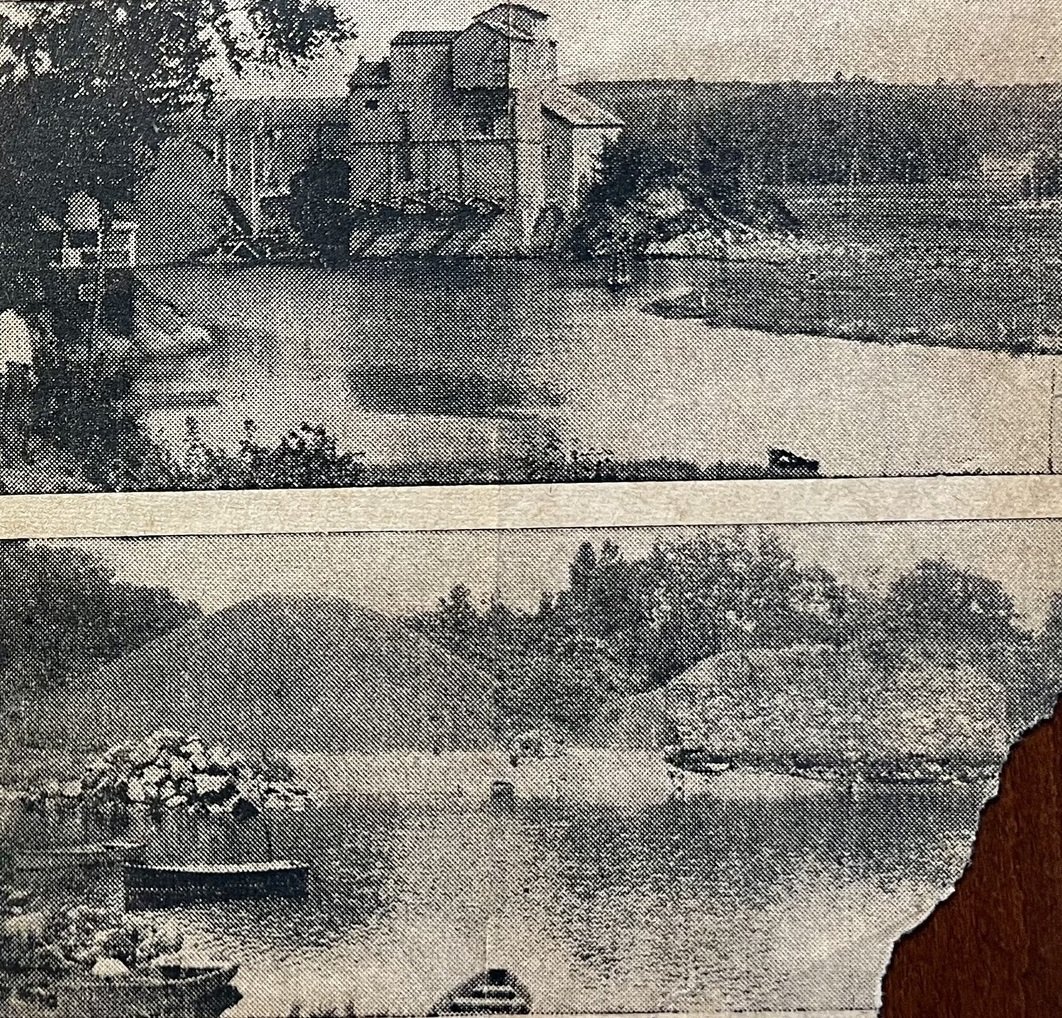

In 1866, sixteen years after the death of the last full-blooded Momauguin native American, “Half Mile Island,” as it was then called, was still an inaccessible wilderness. Bordered by Bradford Creek to the west and the Farm River to the east, the only land access was a narrow horse trail that would later be called Cosey Beach Avenue.

At this time, Daniel Palmer built the first home on what is now known as Whaler’s Point, or approximately the top third of the island. That home exists there today, although greatly altered. After the Palmers moved to the East Haven green, Mr. Palmer still owned most of Half Mile Island.

That same year, Dennis Mansfield, after roughing it on the island for several years, decided to start a shore resort facility. Renting three of the southern acres, Dennis built boating, fishing and hunting facilities, as well as a home for his family. He carved out a primitive road from Short Beach Road to accommodate horse-drawn stages and wagons. Soon he and his wife were selling lobsters and shore dinners to boaters and sportsmen. By the 1870s his resort became known as “Mansfield Grove.”

The Mansfields built the two-story Rocky Point Hotel in 1879 which featured a dozen upstairs bedrooms, a sweeping veranda, and plentiful rocking chairs for guests to relax.

When Dennis died in 1889, his estate was divided into three sections that eventually became what we have today. The twelve northernmost acres and cottages became Shepherd’s Grove (now Whaler’s Point); The remainder, which included the hotel, three cottages and a boathouse, as well as fourteen boats, two fish cars, three horses, seven cows, six pigs, etc., etc., became the property of Caroline Mansfield, who carried on the resort’s operation. The hotel survived the hurricane of 1938, and finally met its end when it burned down the following year.

CHAPTER 4: The Industrial Revolution

Now our attention turns away from colonization and towards the Industrial Revolution and the entrepreneurial spirit that characterized the time period. While historians may disagree on exact dates, Connecticut entered the industrial age sometime around 1780 and fully embraced it between 1820 and 1830.

The Farm River was essential for many local commercial enterprises. It has been used for navigation by a fertilizer factory, stone quarry, paper mill, saloon, salt hay harvesting, and by fishermen and boating enthusiasts for centuries. During colonial times it served as home to a swine farm, and even an elevated area known as Beacon Hill sported a lighthouse for safe navigation downstream to Long Island Sound.

Farmers raised cattle and horses primarily for their hides, and shoe making became an early and extensive business along the river from New Haven almost to the coast. At first, sweepers used to sweep trimmings into the water; eventually the smell of rotten leather became overpowering and city fathers had to fill in the riverbanks.

The low frame building on the west bank of the Farm River on Route 1, across from the Twin Pines Diner is the site of the first Iron Mill in Connecticut, and the third in the United States. Established in 1655, the forge was converted into a fulling and carding mill in 1687 by Samuel Hemingway. Over the years the building has been used as an antique shop, laundry, and tea room; recently opened as a European restaurant, Transilvania Restaurant & Bar.

Before 1832, as cattle and horse ranching moved to the “wild wild west” with its open prairies suitable for larger herds, ranching became marginally profitable on the east coast. However, local farmers found an opportunity to raise dairy cows and opened milk producing businesses. Two local businessmen, H. Todd and W. Townsend, decided to bottle milk and deliver it in capped bottles. Customers rinsed the empty bottles and returned them to the same delivery wagon on its next return. And so, here in East Haven, bottled milk was invented and recycling was born. Home milk delivery became an industry model well into the 1960s.

In various locations between North Haven and Branford, there were in these times quarries producing vast amounts of high-quality trap rock. While some was transported by land, most was transported down the Farm River to the Sound. In the Twentieth Century a New York concern bought the quarry to eliminate its competition. Eventually the quarry burned and was closed. Remnants of the ruins exist today along the trolley line.

The land on East Main Street at the foot of Lake Saltonstall was used for a variety of businesses until it was sold in 1681 and converted into a sawmill, turning out planking for wooden ships built in local shipyards on the banks of the Quinnipiac River in Fair Haven. By 1873 it was operating as a brush factory as well, until 1878, when the grist mill, saw mill, and brush mill were all destroyed by fire.

CHAPTER 5: Trolleys and Model “T” s

Originally population growth in greater New Haven was driven by the flow of immigrants fleeing persecution or famine. Others arrived out of a sense of adventure and opportunities in the new land. In 1890, Momauguin was still mostly a wilderness, with only a few sparse farms in the area. Most of the industrial growth surrounded the farms. Except for water access, Mansfield Grove could still only be reached by horse travel over the narrow and primitive road cut out over 25 years earlier. The future of the Mansfield Grove resort did not look promising, lacking the charm and personality of the late Dennis Mansfield. But things were about to change.

According to New Haven Streetcars, a publication of the Shore Line Trolley Museum, “The first street railway began operation in New York City in 1832.” “In May 1861, more than a year before the nation’s capital introduced this new mode of transit, the forty thousand residents of New Haven were furnished with local rail transportation. Street railways made it possible to reach both residential and manufacturing areas.” Thus began a transformational era which saw New Haven’s population more than quadruple between 1861 and 1948.

The initial form of transportation was horse drawn stages, and by 1883 the rails were extended from the East Haven green to the shoreline resorts. This completed the connection between the shore and the New Haven green on Chapel Street. Lake Saltonstall was a transfer point from New Haven to points east. Once the resorts there closed, ridership suffered, and by 1898 a line was extended down Hemingway Avenue to the beach. In order to induce summer riders, the Momauguin Hotel was built and lavishly furnished, including sterling silver table settings from Tiffany’s. All was destroyed in a fire in 1911.

After the 1911 fire, the trolley company extended the rails along Cosey Beach Avenue, terminating at the Bradford Creek foot bridge providing access to the Mansfield Grove Hotel (currently the site of the Four Beaches Condominiums). In later years it was known as the Rocky Point Hotel and was well known for its illegal rums during the Prohibition years.

After the turn of the century, while the trolley company sought ways to sustain ridership, a new form of transportation independence struck the country like a storm. Henry Ford’s “Model T” automobile offered affordable transportation to the average American, free from the constraints of rail lines and the confines of schedules. Between 1913 and 1927, Ford sold more than 15 million cars.

After World War I, the automobile began to reduce trolley ridership. To offset this, around 1922, the trolley company encouraged the construction of a dance hall on Mansfield Grove. Once built, the hall saw many uses, from dances to church services. On weekend afternoons one-reel movies were shown, accompanied by the piano player who could adapt the music from action to romance, or to the charge of cowboys and Indians. Later the hall was used for roller skating, and eventually as a restaurant night club. With the great band era just beginning, Rudy Valley, Cab Calloway and Glenn Miller toured here, as did other celebrities of the time.

Eventually the dance hall burned down and was razed; the tracks were removed from the streets to accommodate cars. No more would young boys hang on the back of the trolleys, stealing a ride and catching the ire of the motorman when he spotted them.